How sufficiency-driven models can alter the clothing industry amidst a fast fashion frenzy

Threads of change

Authors: Katherine Lewis, Dr. Anh Mattick, Barbara Klobucaric

Hier finden Sie den Artikel als PDF inkl. Grafiken

The textile industry is a significant contributor to the global economy, comprising three market segments: household textiles, technical textiles, and fashion textiles. The collective market value of these sectors is approximately 1.4 trillion USD, with a global workforce of 300 million jobs and the potential to contribute up to 30 % of some countries’ GDP. However, the environmental impact of business on this scale is significant, with the generation of waste, pollution, and exorbitant water consumption being particularly concerning [1]. The production of textiles, whether using organically grown and processed cotton or chemically produced synthetics like nylon, requires substantial amounts of water, contaminates soil and water supplies with chemicals and pesticide residues, and emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere [2]. The finite supply of resources necessitates a fundamental transformation in global production and consumption patterns.

The terms »sustainability« and »sustainable development« have become ubiquitous in contemporary discourse. However, the precise meaning of sustainability is often subject to interpretation, with numerous definitions emerging from various sources. The concept of sustainability has been studied for decades, but its connection to ecological development is more recent. It focuses on nature's ability to regenerate resources in some contexts, like lumber, but not in others, such as fresh water. Sustainability, in this sense, refers to maintaining the supply of both renewable and non-renewable resources at a consistent rate [3]. In the context of business, sustainability can be operationalized through a multitude of methods and levels of severity, with the potential to encompass an enterprise's entire business model or a single product. For example, a clothing retailer may endeavor to integrate sustainability into its business practices by transitioning from selling inventory shipped from overseas to selling locally manufactured clothing, reducing the business’s carbon footprint.

The concept of sufficiency represents taking more profound approaches to sustainable business practices that require a »fundamental shift in the purpose of business and almost every aspect of conduct« rather than a patch-work approach [4]. Sufficiency is an ecological-economic concept that focuses on sufficiently satisfying the demand of consumers in balance with planetary resource boundaries [5]. Application of sufficiency-oriented business operations necessitates using resources as efficiently as possible, to produce less waste and reduce environmental harm throughout the entire supply and value chain, as well as taking the products´ life cycle into consideration. Sufficiency can serve as a powerful catalyst for business model innovation because it fundamentally reimagines the way value is created and delivered. Unlike efficiency and consistency strategies, which aim to provide the same utility in more sustainable ways, sufficiency challenges businesses to rethink the entire value proposition by focusing on altering the different aspects of utility that products and services offer [6]. This shift in thinking welcomes vast opportunities for innovation, as it requires businesses to explore new ways of meeting needs with fewer resources, thereby encouraging the development of novel products, services, and business practices. For example, shifting from driving a car to riding a bicycle as a mode of transportation does not only change the necessity of getting from point A to point B; it redefines the associated benefits, such as promoting health, reducing environmental impact, and simplifying daily life (e.g., zero gasoline expense, zero auto insurance requirements, less machine maintenance). By prioritizing these different aspects of utility, businesses may innovate in ways that align with sustainability goals, creating new markets and customer experiences that reflect a deeper understanding of value. In this way, sufficiency serves as a vehicle for innovation, driving the creation of business models that are not only economically viable but also socially and environmentally sustainable. Stimulating demand for products in a sufficiency-driven business model can be accomplished by engaging with consumers through marketing and advertisement that showcases and advocates for the importance of sustainability and the multi-faceted benefits [7]. Subsequently, the adoption of sufficiency-driven thinking necessitates a shift in perspective regarding consumption. It requires that businesses prioritize the creation of demand for only what can be deemed necessary, rather than the generation of excess demand for products and services that are merely desired [8].

In the context of the clothing industry, the antithesis of sufficiency-driven business models are fast fashion-oriented models that cater to fleeting trends and immediate, albeit short-sighted, desires in clothing styles. These models are characterized by fast production delivery and low production costs [7]. The phenomenon of fast fashion is the inevitable culmination of a confluence of factors, including the rise of online shopping, the global reach of brand names, and the outsourcing of manufacturing to low-cost locations. Indeed, many international clothing brands purchased by the average consumer can be classified as fast fashion, making it a seemingly unavoidable trend. The further embrace of fast fashion would yield a multitude of implications, including environmental degradation, labor exploitation, economic influences, and permanent shifts in consumer behavior [4]. While the negative impacts of fast fashion are evident, every culture inevitably gives rise to its own counterculture. The advent of fast fashion has given rise to a growing awareness and demand for sustainable fashion, as well as a consumer focus on companies that demonstrate sufficiency-minded business models or products.

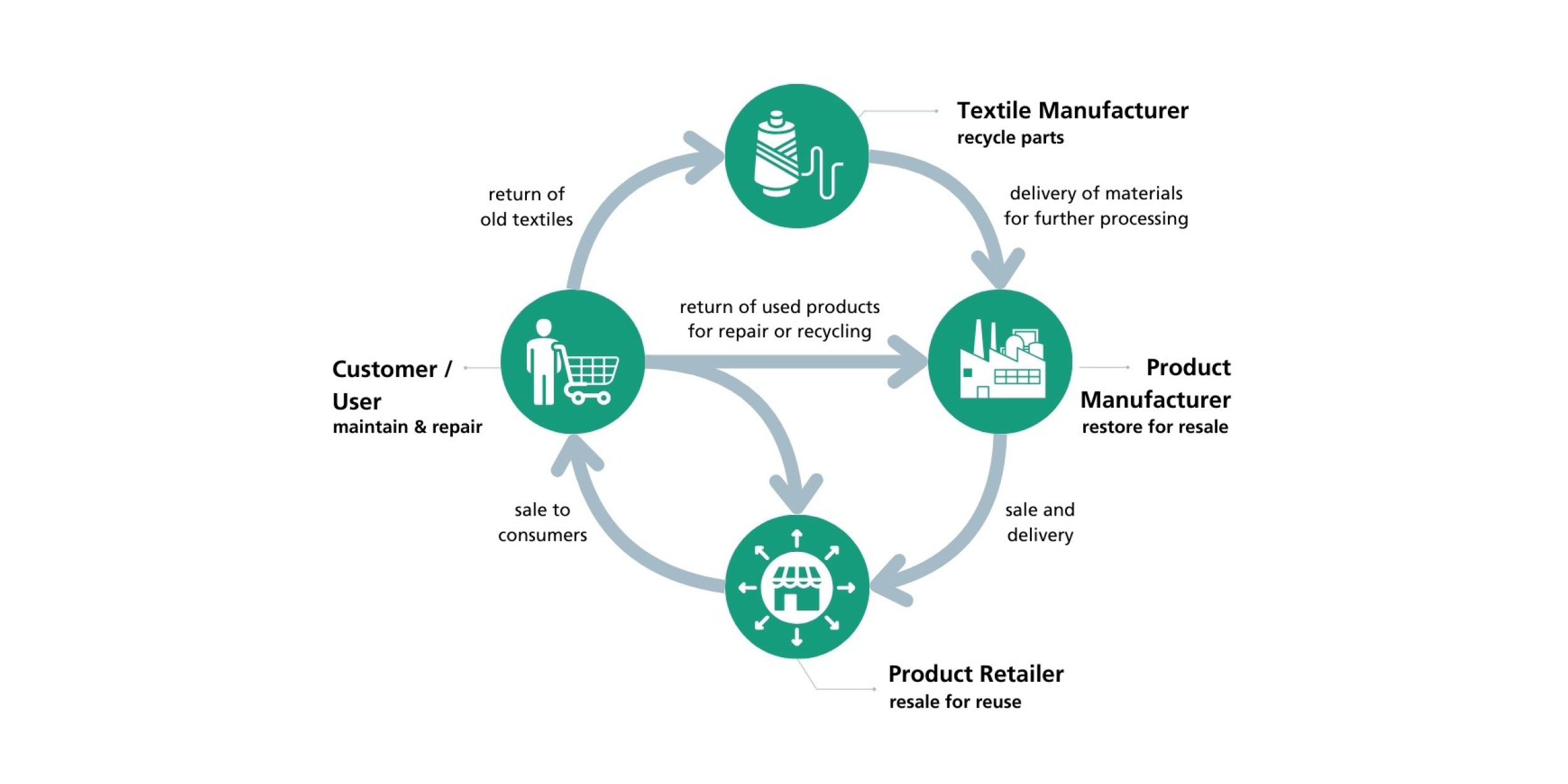

Circular economy practices have gained significant attention in recent years, becoming a hot topic in research and policymaking as industries look to sustainable solutions for global resource challenges. A circular economy system is designed to replace the end-of-life system for products by reusing, repairing, recycling, and recovering materials in production or distribution to further commodify them [3]. The goal is for products to endure several cycles of use or ownership, with disposal as a last resort option [9]. Circular economy practices, which emphasize recycling and reusing materials, are gaining traction, but may still contribute to increased resource consumption if overall product and service demand is not curbed [7]. Recycling alone cannot resolve the environmental crisis. Therefore, it's crucial to adopt a sufficiency-driven business model that directly tackles unsustainable consumption [10].

Within the fashion industry, circular economy systems can be implemented through choosing to manufacture and market higher quality clothing without built-in obsolescence wherein clothes fall apart easily due to low-quality tailoring or material. Clothing brands can also choose to purchase better quality inventory and market items as timeless, classic staples for one’s wardrobe. Battling obsolescence and embracing a circular business model can manifest through innovation that may embrace either long term ownership or short-term ownership. Slow fashion does not necessitate the lifelong usage of an item by a single individual. Clothing rental is a service operated by many fashion companies large and small. Renting provides customers with short-term ownership of clothing and accessories intended for special or unique occasions, such as evening dresses, gowns, and other formal wear. Clothing rental is one sustainability-minded service that even H&M, one of the largest international clothing retailers, offers as part of the company’s initiative to become completely circular with a climate-positive value chain by 2040 [11]. H&M may serve as an example of how meticulous planning, strategic partnership, and commitment to transformation can enable a company known for fast fashion to gradually adopt more sufficient practices over time. While H&M’s rental services and recycled material clothing labels could be critiqued for ‘green washing’ in the name of sustainability by ultimately creating more consumption through the addition of extra production, it is evident that the company has long-term goals and has made significant progress towards carrying exclusively recycled or sustainable textiles [12]. Whether H&M can turn its sustainability vision into reality by 2040 is still an open question.

Every application of a circular economy model is not flawless. In fact, some occurrences are open to critical assessment. For example, models that place an excessive burden on the consumer to close the loop due to poorly established infrastructure, or models that expend resources by commodifying reused goods, warrant further examination. Exporting used clothing overseas, while ostensibly a form of reuse, is not an effective means of reducing CO2 emissions in the short term and can in fact exacerbate environmental and social issues in the regions affected. This practice frequently shifts the burden of waste management from developed to developing countries, where the infrastructure to guarantee the proper allocation and distribution of imported clothing may be insufficient [13]. This issue can be mitigated by implementing a circular economy system on a local level with better infrastructure in place. However, the practice of clothing export highlights the urgent need to prioritize demand and production reduction in business operations over reuse-oriented models. In light of these considerations, it is incumbent upon companies to pursue a model that is in alignment with their product and vision.

»Every time I have made a decision that is best for the planet, I have made money« – Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia founder [14].

Corporate responsibility towards sustainability does not have to come at the expense of profit. Despite navigating through regulations and extra costs, innovating business models to incorporate sufficiency factors or circular systems has been proven. Outdoor apparel giant Patagonia is renowned for being one of the most socially responsible companies in the world. This reputation is largely attributed to the company’s embrace of sustainability principles, including the concept of sufficiency, as a guiding star for its business practices. Additionally, Patagonia takes pride in their corporate identity and public position as a leader in circular economy practices, which are integrated into their unique selling point of outdoor apparel among competitors. Patagonia's mission statement echoes the importance of sufficiency as a driving factor, articulating their commitment to »build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis«.

As well as advertisements that beckon consumers to, “reimagine a world where we take only what nature can replace”. One inventive service Patagonia provides is the guarantee to repair any well-worn garments through collaboration with clothing repair partners, educate customers on how to maintain and repair their garments, or sell their used apparel back to Patagonia through an internal secondhand system they brand as »Better than New« clothing [15]. Patagonia's public shift towards prioritizing corporate social responsibility and implementing slow fashion and anti-obsolescence services like clothing recycling served as a marketing campaign, enabling the company to differentiate itself from other retailers. However, the appeal of sustainability extends beyond mere public relations and marketing campaigns. The provision of the repair and resale service for used Patagonia items, along with a comprehensive overhaul of the company's identity and workplace practices, has led to a notable increase in profitability [16]. Although they are benefiting from global brand recognition, the positive attention they received from consumers for innovating their business model demonstrates that genuine sustainability measures are more effective than purely commercial strategies. Patagonia correctly recognized that its customer base, made up of people who enjoy spending time in nature, would be impressed and show brand loyalty to a company with a top-down approach to protecting the natural environment. Nevertheless, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard maintains that every business can identify a distinctive advantage in embracing sustainability. Chouinard suggests that this should be regarded as an integral aspect of corporate responsibility, rather than as a form of voluntary corporate philanthropy [13]. Given that all businesses contribute to pollution and use non-renewable resources, there is an opportunity for all types of businesses to adopt innovative and strategic approaches to sustainability.

While Patagonia and luxury clothing cater to the upper end of the price spectrum, not all ventures into circular business models require heavy consumer spending. Secondhand clothing has become an accessible way for people of all budgets to participate in the circular economy by purchasing used garments and extending their life cycle beyond a single owner. In a 2023 case study, the Portuguese secondhand clothing store Humana was found to have sold 1,426 tons of garments over a four-year period. The researchers calculated that the store's sales conserved 80,342,082 cubic meters of water and 18,574,473 kilograms of CO2-equivalent emissions that would result from the purchase of newly produced clothing or from old clothing being disposed of in landfills [17]. However, the same case study reports an unfortunate ratio wherein the intake of used clothing greatly exceeds the amount of garments that are eventually sold. This significant imbalance between supply and demand could be rectified by widespread reduction of fast fashion production, or through business innovation and social entrepreneurship. The adage »necessity breeds innovation« rings especially true in the current context of secondhand clothing. As the industry faces challenges like oversupply, environmental concerns, and shifting consumer attitudes, these pressures are creating fertile ground for social entrepreneurs to introduce fresh ideas, innovative marketing strategies, and transformative business models that can revitalize the public image and consumer perception of secondhand clothing as socially responsible fashion.

These examples demonstrate that there is scientifically supported demand for companies in the clothing industry to consider new business models that showcase second-hand avenues for clothing, clothing rental or subscription, and clothing repair for the sake of energy consumption, waste avoidance, and resource management. The current scientific literature suggests avenues for future research, such as investigation into pathways to better overcome industrial ambivalence towards sustainability, and the challenges companies may face when attempting to incorporate sufficiency-guided principles into their organization. Sufficiency is a concept that can be applied to many industries outside of fashion and textiles, such as the food industry or logistics, packaging and delivery. Exploring the applicability of sufficiency-oriented business models in these industries is welcomed.

Transformation

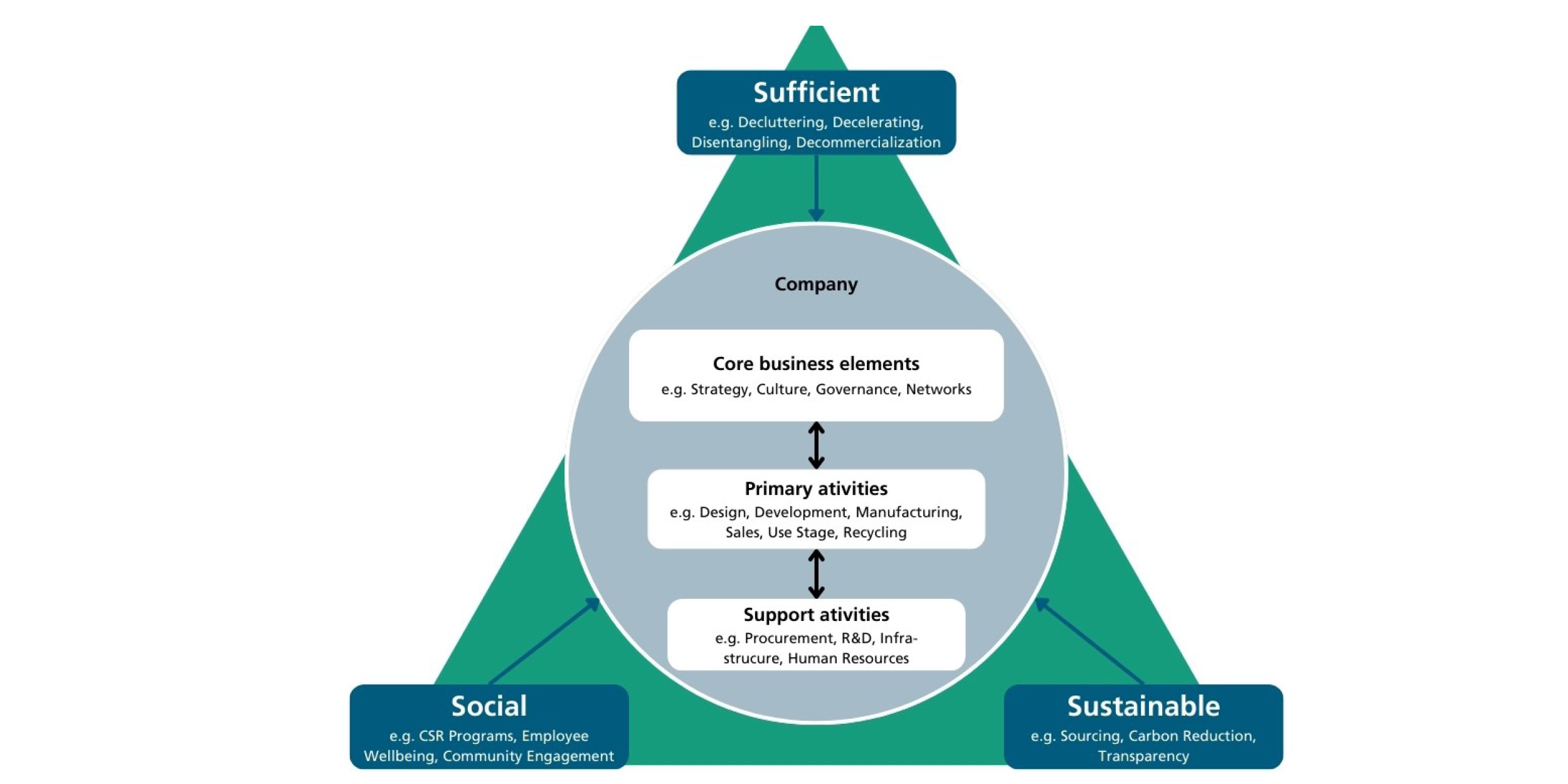

The S³ Framework (see Figure 2) is a dynamic initiative providing companies with a comprehensive and actionable blueprint for integrating sustainable, social and sufficiency-oriented criteria (see Table 1) into every aspect of operations.

Sustainable: This principle focuses on enhancing resilience by utilizing fewer and more localized resources, fostering enduring stakeholder relationships, and prioritizing long-term value over immediate profits. |

Social: This aspect emphasizes the importance of embracing ethical practices and corporate social responsibility to positively address how a business can best interact within the community it exists in. |

Sufficient: The final principle underscores the necessity of operating within planetary limits by optimizing resource use and systematically reducing environmental impact. This involves simplifying and streamlining supply chains, such as by eliminating unnecessary processes, reducing excess or environmentally harmful material use, or shifting to region-focused supply chain strategies. Evaluating long-term objectives, planning sustainable growth, and effectively managing product demand. |

As the fashion sector confronts mounting environmental and social challenges— excessive waste, resource depletion, and labor issues—our framework provides businesses with the essential tools to effectively address these urgent concerns. By embedding sufficiency in critical areas such as procurement, production, organizational culture, and employee training, we advocate for a transformative approach that transcends incremental improvements, fostering a holistic commitment to sustainability.

The S³ Framework emphasizes the interconnectedness of various business units, ensuring that sustainability efforts are mutually reinforcing. By prioritizing procurement strategies that favor sustainable materials, optimizing production processes to minimize waste, and implementing marketing efforts that promote responsible consumption, the framework creates a cohesive approach that enhances overall organizational performance. This comprehensive integration is crucial for driving a unified commitment to long-term environmental and social goals, ensuring that all aspects of the organization work in harmony toward shared sustainability objectives. The S³ Framework provides a robust foundation for companies to assess and maximize their potential for sufficiency, positioning them as leaders in the societal shift toward sustainability within planetary limits. While still evolving, our framework aims to advance the understanding and adoption of sufficiency as a critical element of sustainable business strategy. We have identified this is particularly relevant for the fashion industry, where the need for fundamental change is most urgent considering the meteoric rise of fast fashions trends. By working through the framework, businesses can effectively mitigate their environmental and social impacts and build more resilient, more innovative organizations capable of thriving in a resource-constrained world.

The Next Steps

Innovative solutions are hard to come by exclusively through internal knowledge. As seen in the real industry examples, companies often engage in cooperative partnerships with consulting actors or external governmental actors to workshop strategies for implementing transformative change in organizational philosophy, values, and intentions towards the production of sustainable products without compromising productivity and profit.

As this article highlights, sufficiency-driven business models and circular economies are not universally applicable to all companies. Each organization operates within its own unique context, influenced by industry dynamics, target consumer base, and most importantly, the intended use and impact of products. Consequently, those in positions of organizational leadership must engage in creative thinking and strategic foresight before developing or transforming their business model. This is to ensure the creation of a model that is in harmony with the product and the vision of the organization. Consulting with experts can be invaluable in this process, as they bring specialized knowledge-based frameworks and external perspectives that can help identify the most effective ways to tailor sufficiency factors to a company's specific needs.

Hier finden Sie den vollständigen Artikel als PDF inkl. Fußnoten / Quellenangaben und Grafiken

Letzte Änderung: